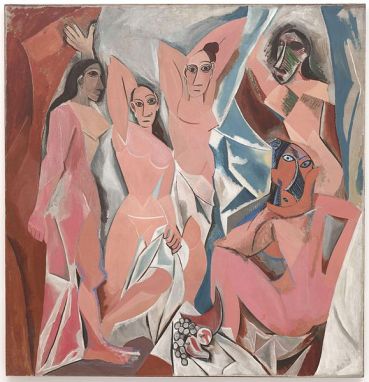

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Europeans were discovering African, Polynesian, Micronesian and Native American art. Artists such as Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso were intrigued and inspired by the stark power and simplicity of styles of those foreign cultures. Around 1906, Picasso met Matisse through Gertrude Stein, at a time when both artists had recently acquired an interest in primitivism, Iberian sculpture, African art and African tribal masks. They became friendly rivals and competed with each other throughout their careers, perhaps leading to Picasso entering a new period in his work by 1907, marked by the influence of Greek, Iberian and African art. Picasso’s paintings of 1907 have been characterized as Protocubism, as notably seen in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the antecedent of Cubism.

Paul Cézanne, Quarry Bibémus, 1898-1900, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany

The art historian Douglas Cooper states that Paul Gauguin and Paul Cézanne “were particularly influential to the formation of Cubism and especially important to the paintings of Picasso during 1906 and 1907”. Cooper goes on to say: “The Demoiselles is generally referred to as the first Cubist picture. This is an exaggeration, for although it was a major first step towards Cubism it is not yet Cubist. The disruptive, expressionist element in it is even contrary to the spirit of Cubism, which looked at the world in a detached, realistic spirit. Nevertheless, the Demoiselles is the logical picture to take as the starting point for Cubism, because it marks the birth of a new pictorial idiom, because in it Picasso violently overturned established conventions and because all that followed grew out of it.”

The most serious objection to regarding the Demoiselles as the origin of Cubism, with its evident influence of primitive art, is that “such deductions are unhistorical”, wrote the art historian Daniel Robbins. This familiar explanation “fails to give adequate consideration to the complexities of a flourishing art that existed just before and during the period when Picasso’s new painting developed.” Between 1905 and 1908, a conscious search for a new style caused rapid changes in art across France, Germany, Holland, Italy, and Russia. The Impressionists had used a double point of view, and both Les Nabis and the Symbolists (who also admired Cézanne) flattened the picture plane, reducing their subjects to simple geometric forms. Neo-Impressionist structure and subject matter, most notably to be seen in the works of Georges Seurat (e.g., Parade de Cirque, Le Chahut and Le Cirque), was another important influence. There were also parallels in the development of literature and social thought.

In addition to Seurat, the roots of cubism are to be found in the two distinct tendencies of Cézanne’s later work: first his breaking of the painted surface into small multifaceted areas of paint, thereby emphasizing the plural viewpoint given by binocular vision, and second his interest in the simplification of natural forms into cylinders, spheres, and cones. However, the cubists explored this concept further than Cézanne. They represented all the surfaces of depicted objects in a single picture plane, as if the objects had all their faces visible at the same time. This new kind of depiction revolutionized the way objects could be visualized in painting and art.

Jean Metzinger, La Femme au Cheval, Woman with a horse, 1911-1912, Statens Museum for Kunst, National Gallery of Denmark. Exhibited at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants, and published in Apollinaire’s 1913 The Cubist Painters, Aesthetic Meditations. Provenance: Jacques Nayral, Niels Bohr

The historical study of Cubism began in the late 1920s, drawing at first from sources of limited data, namely the opinions of Guillaume Apollinaire. It came to rely heavily on Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler’s book Der Weg zum Kubismus (published in 1920), which centered on the developments of Picasso, Braque, Léger, and Gris. The terms “analytical” and “synthetic” which subsequently emerged have been widely accepted since the mid-1930s. Both terms are historical impositions that occurred after the facts they identify. Neither phase was designated as such at the time corresponding works were created. “If Kahnweiler considers Cubism as Picasso and Braque,” wrote Daniel Robbins, “our only fault is in subjecting other Cubists’ works to the rigors of that limited definition.”

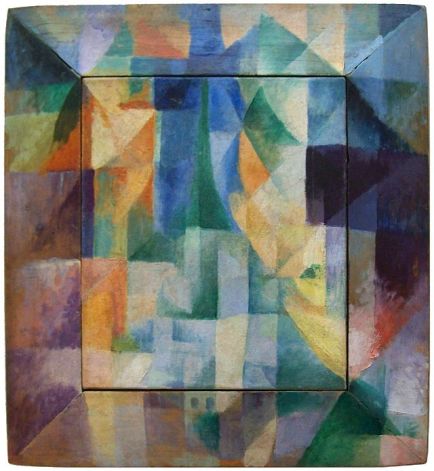

The traditional interpretation of “Cubism”, formulated post facto as a means of understanding the works of Braque and Picasso, has affected our appreciation of other twentieth-century artists. It is difficult to apply to painters such as Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Robert Delaunay and Henri Le Fauconnier, whose fundamental differences from traditional Cubism compelled Kahnweiler to question their right to be called Cubists at all. According to Daniel Robbins, “To suggest that merely because these artists developed differently or varied from the traditional pattern they deserved to be relegated to a secondary or satellite role in Cubism is a profound mistake.”

The history of the term “Cubism” usually stresses the fact that Matisse referred to “cubes” in connection with a painting by Braque in 1908, and that the term was published twice by the critic Louis Vauxcelles in a similar context. However, the word “cube” was used in 1906 by another critic, Louis Chassevent, with reference not to Picasso or Braque but rather to Metzinger and Delaunay:

“M. Metzinger is a mosaicist like M. Signac but he brings more precision to the cutting of his cubes of color which appear to have been made mechanically […]”.

The critical use of the word “cube” goes back at least to May 1901 when Jean Béral, reviewing the work of Henri-Edmond Cross at the Indépendants in Art et Littérature, commented that he “uses a large and square pointillism, giving the impression of mosaic. One even wonders why the artist has not used cubes of solid matter diversely colored: they would make pretty revetments.” (Robert Herbert, 1968, p. 221)

The term Cubism did not come into general usage until 1911, mainly with reference to Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay, and Léger. In 1911, the poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire accepted the term on behalf of a group of artists invited to exhibit at the Brussels Indépendants. The following year, in preparation for the Salon de la Section d’Or, Metzinger and Gleizes wrote and published ‘Du “Cubisme”[22] in an effort to dispel the confusion raging around the word, and as a major defence of Cubism (which had caused a public scandal following the 1911 Salon des Indépendants and the 1912 Salon d’Automne in Paris).[23] Clarifying their aims as artists, this work was the first theoretical treatise on Cubism and it still remains the clearest and most intelligible. The result, not solely a collaboration between its two authors, reflected discussions by the circle of artists who met in Puteaux and Courbevoie. It mirrored the attitudes of the “artists of Passy”, which included Picabia and the Duchamp brothers, to whom sections of it were read prior to publication.[4][19] The concept developed in Du “Cubisme” of observing a subject from different points in space and time simultaneously, i.e., the act of moving around an object to seize it from several successive angles fused into a single image (multiple viewpoints, mobile perspective, simultaneity or multiplicity), is a generally recognized device used by the Cubists.[24]

The 1912 manifetso Du “Cubisme” by Metzinger and Gleizes was followed in 1913 by Les Peintres Cubistes, a collection of reflections and commentaries by Guillaume Apollinaire.[25] Apollinaire had been closely involved with Picasso beginning in 1905, and Braque beginning in 1907, but gave as much attention to artists such as Metzinger, Gleizes, Delaunay, Picabia, and Duchamp.

Steinbruch Bibemus, Paul Cézanne

La Femme au Cheval (Woman with a Horse), Jean Metzinger